HOUSING STOCK AND REGIONAL HOUSING NEEDS ASSESSMENT TARGETS

1806-2016 and beyond IN THE County and CITY OF LOS ANGELES

Introduction

This study provides an inventory of the existing housing stock in the City of Los Angeles, categorized by Building Typology and decade built, from 1804 through 2019.

Housing production is directly proportional to zoned capacity. However, exclusionary land use policies, such as reduced zoned capacity or downzoning, parking minimums, etc., have constrained housing production and have favored the largest building types, particularly buildings with 100 or more dwelling units, which represent only 7% of the overall housing production. Further, the production gap in the housing market has negative impacts that affect everybody: deteriorated air quality, increased traffic, unequal access to schools, constraints on the labor pool, deteriorated social capital, etc.

The current housing production target for the City of Los Angeles is nearly half a million (456,643) net new dwelling units by 2029. On average 57,080 net new units are required to be supplied in the City of Los Angeles in order to meet the 8-year RHNA target. By comparison, the observed supply of dwelling units in the decade of the 2010s, which was 4,236 dwelling units in the City of Los Angeles, would need to increase 13 times in order for the RHNA target to be met.

This report sets the foundation for further research and policy questions to be raised, such as, through what specific mechanisms shall the homebuilding industry scale close to 13 times? Who stands to benefit from this industry growth? Are current or planned policies picking winners and losers?

Literature Review

The 2020 Greater Los Angeles Homeless Count by the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority (LAHSA) identified nearly 64,000 homeless individuals, excluding Pasadena, Glendale, and Long Beach. Just over 41,000, or 65%, of those are located in the City of Los Angeles, which experienced a 16% increase from 2019. Public and private resources are being expended in an attempt to mitigate the situation, from $968 M committed or spent under the $1.2 B Proposition HHH bond to $460 M in the Mayor’s budget for Supportive Housing, Bridge Housing, services and facilities for homeless, $85 M in 2018 and $124 M in 2019 from the State of California, etc. However, until the rate of increase in cost of housing continues to outpace household income, more and more homes will continue to face precarious housing conditions and increasing numbers of households will fall into homelessness, as documented by the 2019 US Department of Housing and Urban Development report, “Market Predictors of Homelessness” (Nisar, 2019).

California is home to some of the most unaffordable cities in the country. The root causes in Los Angeles include exclusionary zoning, such as downzoning, lack of policy enforcement, rising construction and development costs, inequitable urban planning, a financial structure favoring nonresidential development, insufficient government spending, and crucially, suppressed housing supply rates. (Taylor, 2015; Morow, 2013; Taylor, 2015; Eikel, 1973; Knapp; 2007; Eikel, 1973; Richman, 2000) Housing cost inflation due to short supply continually increases, exacerbating income inequality and a series of urban ills that range from a loss of regional economic productivity and strains on the labor pool to time spent in traffic and greenhouse gas emissions (Baker et al., 2015)

A synthesis of best practices from a review of academic and policy literature identifies the following five categories to mitigate the housing crisis: Policy Reform, Supply Chain capacity development, Financing, Preservation, and a Paradigmatic Shift in the industry. (Richman, 2000; Lewis, 2003; Morrow, 2013; Taylor, 2015; Mischke, 2016; Brown, 2017; Kahlenberg, 2017; Ling, 2018; Woetzel, 2019; Brooks, 2019; Lee, 2017) Further, a scattered site approach has been identified as a more effective affordable housing strategy, as it allows households of various incomes to integrate into communities more successfully. (Nelson, 2014; Ecker, 2017; Graves, 2011) This report contributes to the body of academic and policy literature by taking a longitudinal approach to inventorize and track all subsidized low income housing units in LA County over time. The results may support neighborhood communities, industry leaders, and government agents in planning and policy formulation for more equitable housing resources in the LA region.

Housing Supply Rates

A report from the California Department of Housing and Community Development concluded that the State falls short of housing production by 100,000 homes per year. (Brown, 2017) The average annual rate of dwelling unit supply in the City of Los Angeles from 2013 through 2019 was only 7,000 units per year, eight times less than the 57,000 unit annual supply rate required of the coming eight year planning cycle under State law, that is, the 2029 RHNA Target. (Rodman-Alvarez et. al., 2020; Yoon, 2020) Further, over 90% of all housing built between 2014 and 2018 are affordable only to households making above the area median income. (Woetzel et al., 2019)

Affordable housing that is subsidized either partially or fully by public and private funds and agencies assists cost burdened households, including seniors, those living with mental health conditions, and so forth.

By 2029, over 259,000 net new units that are affordable to Median, Low, and Very Low Income households are required in the City of Los Angeles, an average of above 32,000 net new affordable units per year. (Yoon, 2020) By contrast, the average supply rate of affordable units in the City of Los Angeles from 2014 to 2018 was 1,500 units per year, a 22nd of the necessary supply rate. (Woetzel et al., 2019; Yoon, 2020). Also, while investigative journalism has recently reported on gross inefficiencies in City driven production of permanent supportive housing and emergency shelters for the unhoused, an accurate inventory of the existing low income subsidized housing stock is necessary in order to identify disparities in the number of affordable housing units per capita in each community.

Pipeline of future projects

As of January 2021, the Mayor’s office reports that there are 7,300 units and 111 projects in development in Los Angeles under Measure HHH. 5,742 are permanent supportive housing for homeless residents and 1,436 are affordable housing for non-homeless, very low income residents. (Garcetti, 2021) Additionally, the LA City Council approved $203M in bonds, not under Triple H, for six developments totaling 609 affordable units. (Sharp, 2020) According to LA City Planning, 4,790 affordable units have been approved in 2020. (Bertoni, 2021)

Methods

Existing dwelling unit data, including number of units, year built, and geographical coordinates were gathered from the Los Angeles County Office of the Assessor tax roll dataset. Subsidized low income dwelling unit data was gathered from the National Housing Preservation Database.

Both datasets were geographically located using ESRI ArcMap tools and intersected with shapefiles for the geographic areas of study, such as the City of Los Angeles, and the City Council Districts 1 through 15. Data points were selected by location, where the centroid of a parcel was within the area of study. Microsoft Excel was used to assemble the data by area of interest and to create the resultant charts.

In 2015, the Southern California Association of Nonprofit Housing (SCANPH) began a database of all affordable housing units in Los Angeles, categorized by funding source. In 2018, the authors of this report built upon this dataset beginning a longitudinal study of all affordable units organized by City in LA County, Los Angeles City Council District, Community Plan Area, and Neighborhood Council Area. A main objective of this inventory is to identify areas bearing an unfair share of the housing burden as well as those areas of greater need by analyzing disparities in rates of units provided per capita and per area. This 2021 updated report is the most recent inventory published regarding affordable housing units in Los Angeles.

Various data sets were gathered and analyzed as part of this inventory. Beds and Permanent Supportive Housing units from the 2020 LAHSA Housing Count are reported separately in order to keep consistent units of measurement among the tables. Further, due to confidentiality issues regarding victims of domestic violence, transition aged youth, and others, the location of these beds are not reported. For example, St. Joseph’s Center is listed as containing a total of 1,389 beds in the categories of Permanent Supportive Housing, Rapid Re-Housing, and Emergency Shelter; 1,089 of those beds are listed in Venice. However, subsequent over-the-phone interviews conducted with key informants clarified that St. Joseph’s Center does not provide housing per se, but rather, acts as a conduit connecting clients with partners who then provide facilities and beds to clients. Also, note that where a CPA straddles the borders of more than one Council District, e.g., West LA in CD 11 and CD 5, the sum total of the CPAs with a centroid in a Council District will not match the total count for the Council District. In his 2013 dissertation, Dr. Greg Morrow conceptualized the City of Los Angeles as four quadrants: West and East Valley, West and East LA, which includes what was previously referred to as South Central.

Results

Affordability

The affordability sub-score represents the percent change in the average sales price per square foot of properties in each CPA. Data for this indicator come from MLS Title Company sales dataset for LA County. Price change represents the change in price per square foot from 2000-2015. The affordability percentile score is then scaled from 1-10 by dividing all results by the highest value and multiplying by 10.

Environmental Health

The environmental risk sub-score represents indicators of pollution burden and hazards, including: Ozone Concentrations, PM 2.5 Concentrations, Diesel PM emissions, Drinking Water Contaminants, Pesticide Use, Toxic Releases from Facilities, Traffic Density, Cleanup Sites, Groundwater Threats, Hazardous Waste, Impaired Water Bodies, and Solid Waste Sites and Facilities. Data for the Environmental Risk sub-score all come from CalEnviroScreen data. As socioeconomic factors are already considered in the Opportunity sub-score, Environmental Risk score draws only on the Pollution and Hazards data from CalEnviroScreen. Each CPA takes on a sum or average score of the census tracts that fall within it. As CPAs with lower environmental risk are more desirable for housing, results for each sub-indicator are multiplied by -1 to reverse the sign before calculating percentile scores between CPAs. The total Environmental Risk Score represents the average percentile score of each CPA for each of the twelve environmental risk sub-indicators. The average percentile score is then scaled from 1-10 by dividing all results by the highest value and multiplying by 10.

Transit

The transit sub-score combines an indicator for transit quality (percent of CPA area that falls within different TOC incentive tiers) and an indicator for the commuter-jobs balance (the proportion of commuters coming into and out of the CPA). Areas were weighted by increasing tier. As places that fall into a Tier 4 zone have better transit access than places that fall into a Tier 1 zone, scores were weighted accordingly. Land area within Tier 1 is unweighted, land area within Tier 2 receives a weight of 1.25, land area within Tier 3 receives a weight of 1.5, and land area within Tier 4 receives a weight of 1.75. These weighted areas are summed and divided by the total CPA area for a final percent area within TOC boundaries score. Inflow/outflow data were procured from the U.S. Census “On the Map” service. The indicator score represents the proportion of commuter inflow to commuter outflow in the CPA. CPAs with the highest inflow:outflow proportion represent places that should have more housing, so that incoming commuters can be closer to work and travel less. Where in-commuting exceeds out-commuting, the proportion will be greater than one. This represents a CPA that needs more housing. Where out-commuting exceeds in-commuting,the proportion will be less than one. This represents a CPA that already provides housing to surrounding job centers.

The total Transit Score represents the average percentile score of each CPA for transit quality and commuter balance. The average percentile score is then scaled from 1-10 by dividing all results by the highest value and multiplying by 10.

Downzoning

The downzoning sub-score consists of two indicators: the percent change in zoned population capacity, and the current unit density. Change in zoned capacity data is taken from Greg Morrow’s 2013 dissertation, “The Homeowner Revolution.” Morrow (2013) shows that Community Plans in Los Angeles went through three rounds of updates between the 1970s and early 2000s. Change is calculated using the difference between the zoned capacity of each CPA according to community plan updates passed in the 1970s compared to the zoned capacity in the plan updates passed in the late 90s and early 2000s. Areas with negative population capacity change (i.e. evidence of downzoning) are considered more desirable for housing. Therefore, results are multiplied by -1 to reverse the sign before calculating percentile scores between CPAs. Unit density data is calculated by summing the number of units of all parcels within the CPA, as listed on the 2014 LA County Assessor Tax Roll. The total downzoning score represents the average percentile score of each CPA for change in zoned capacity and unit density. The average percentile score is then scaled from 1-10 by dividing all results by the highest value and multiplying by 10.

Opportunity

The opportunity sub-score combines three indicators: median household income (as a proxy for service quality), school quality, and the number of jobs in the CPA. Household income data come from the 2015 American Community Survey. MHI for each CPA was calculated as an average of all the census tracts that fall within the CPA. The number of jobs in each CPA was calculated using the U.S. Census “On the Map” web tool. Data for the school quality indicator represent School Quality Improvement Index scores published by the California Office to Reform Education in 2016. This more comprehensive scoring system replaced API in 2013. Each attendance boundary (elementary, middle, and high school) is given an average score of the schools that fall within it, weighted by number of students. Each CPA receives an average score of the elementary, middle, and high school attendance boundaries that intersect it. The total Opportunity Score represents the average percentile score of each CPA for MHI, number of jobs, and school quality. The average percentile score is then scaled from 1-10 by dividing all results by the highest value and multiplying by 10.

* Not all attendance boundaries contained a school in the dataset. In cases in which no school/score was available, the attendance boundary was assigned an average value for the district.

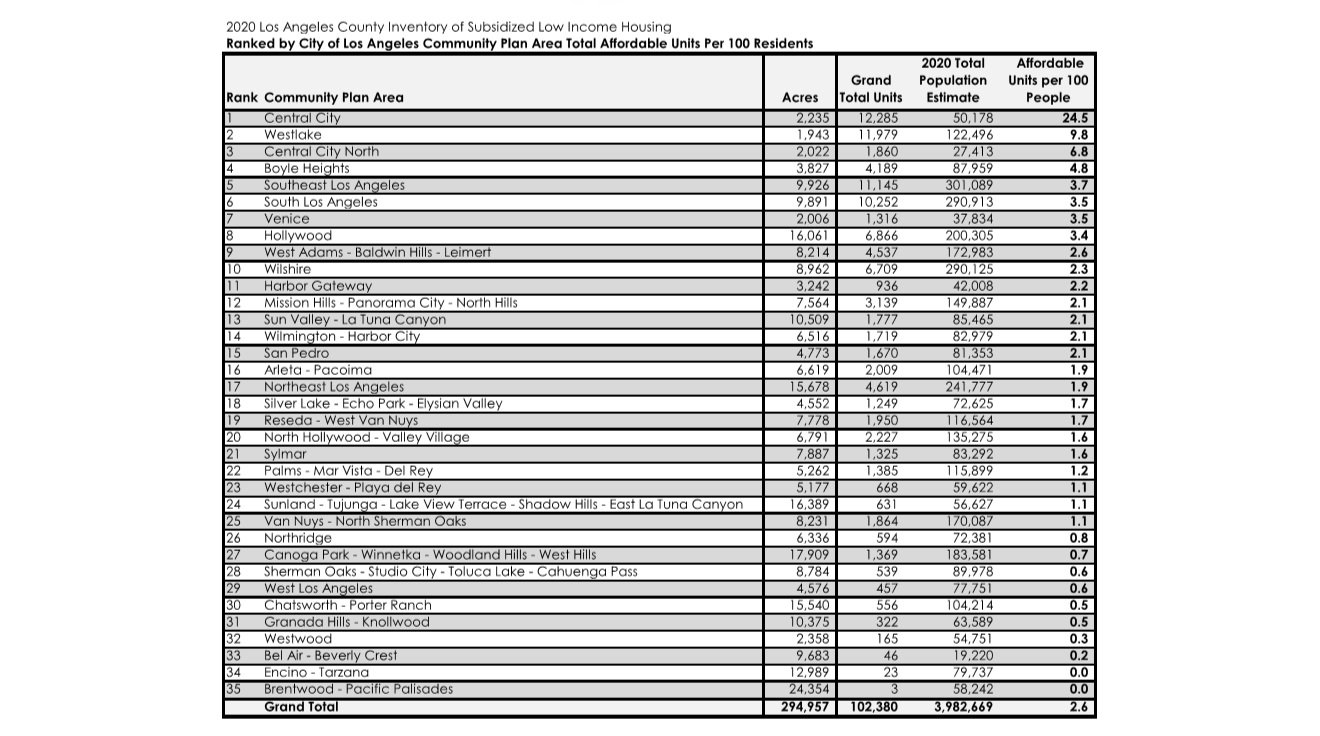

As of 2020, there are a total of 146,473 subsidized low income units spread out around 2,870 addresses, funded or managed by one to several of 15 entities or programs. LAHSA counts 46,723 beds or services under one or several of six types, including Permanent Supportive Housing. There are geographic and other disparities in the preponderance of affordable units by area.

A disproportionate amount of affordable housing is located in the Eastside and East Valley quadrants of Los Angeles. In 2020, the Eastside quadrant represented the highest amount of subsidized low income housing in the city, with 71,000 units or 77% of the total. By contrast, the Westside’s share of affordable housing units, approximately 4,100 units, is 5% that of the Eastside quadrant. The West Valley quadrant fared similarly to the Westside, containing only a few hundred more affordable units, approximately 4,700. As will be noted below, there are disparities among Community Plan Areas (CPA) within quadrants. For example, Venice as a whole contains 3.3 units per 100 persons, on par with the 3.5 units per 100 overall on the Eastside. Results per Los Angeles City Council District show that the 14th District, represented by Councilperson De Leon, contains the majority of affordable housing units with 16,342. District 14 includes Skid Row and is home to some of Los Angeles’s most vulnerable populations. Compare this to District 5, represented by Councilperson Koretz, which contains just 608 of the share of affordable units. In stark contrast to District 14, District 5 is home to Bel Air and some of the most affluent neighborhoods in Los Angeles. Additionally, in Council District 11, which has a per capita rate of 1.2 affordable units per 100 people, Venice bears a disproportionate share with 3.3 units per 100 people.

Observations:

Housing stock reported by decade may be seen as a proxy for rate of development over time; demolished dwelling units and losses due to conversion are omitted from the results, however, the relative quantities of extant dwelling units per decade provide an indication for the rate of development at the time and can be cross referenced with US Census Bureau Data.

According to the Office of the Assessor, there are 1,355,044 existing dwelling units in the City of Los Angeles built from 1804 through 2019. Supply has decreased from a high of 245,051 in the decade of the 1950s, to a low of 47,636 in the decade of the 1990s, and has leveled out since then. Dwelling unit production in the decade of the 2010s was 35% lower than all of the remaining dwelling units from the decade of the 1930s. Two out of the last three decades have produced less units than the decade of the Great Depression. The decade of the 2000s produced 3% more dwelling units than those which remain from the 1930s.

The decade of the 1920s represents a boom in the supply of dwelling units in the City of Los Angeles and ranks third out of the last 12 decades observed in the data. The single highest decade of dwelling unit production was that of the 1950s, which was responsible for the supply of nearly one fifth of all remaining dwelling units in the City of LA. The decade of the 1960s is a near third, with 16% of the City of LA housing stock, yet the spread of building types is interesting in that single family housing production declined whereas low-rise multifamily housing production increased.

In the 1960s, buildings with less than 50 units excluding single family dwellings make up 61% of all dwelling units from this decade. By contrast, in the decade of the 2010s, the same building types (2 through 49 units per building) made up only 29% of the overall housing from that decade; buildings with greater than 100 units made up nearly half, 43% of all dwelling units, and the number of dwelling units from 2010 is 80% less than the decade of the 1960s. In other words, the supply of dwelling units today is dominated by the largest building types yet the amount of supply is 1/5 of the housing stock from the 1960s, 1/6 the stock of the 1950s, and perhaps most alarming of all, dwelling unit supply in the last decade was only 2/3 the stock from the 1930s.

Conclusions

The adverse impacts of the housing production shortage affect all socioeconomic strata in the region. Policies have constrained housing supply and have favored building types with more than 100 dwelling units per building yet the supply rates are below Great Depression era levels. Whereas 93% of all dwelling units in the City of LA’s housing stock are in buildings with 99 or less units per building, local policies tend to favor building types with greater than 100 dwelling units. Multi-family housing buildings, from duplexes through 99 units or less, represent the majority (54%) of all dwelling units in the City of Los Angeles. Among these, buildings with two to four units represent the largest share, with 13% of all dwelling units in the City of Los Angeles.

A review of best practices to bridge the housing production gap in the City of Los Angeles necessitates a detailed inventory of dwelling units by age and building type. This report contributes to scholarly and policy literature in this field. In order to scale housing production from its recent numbers to those required to meet the 2029 RHNA target, the decades of highest production, that is the 1950s and ‘60s provide a valuable study model.

A more equitable distribution of affordable housing is desirable in the City of Los Angeles and the broader region. The affordable housing shortage is caused by the same forces at play in the overall housing shortage. Where some communities bear an unfair share of the housing burden, concentrations of poverty and unequal access to resources result. Fiscal resources are not sufficient to develop the needed affordable housing. For example, the City of LA would have to increase its annual budget threefold and then dedicate that in its entirety to affordable housing development in order to build the number of units necessary at the City’s cost of unit delivery. Conversely, modest policy reforms that affirmatively further fair housing and alleviate the need for subsidized low income housing, such as restoring development rights to land across the City in order for Naturally Occurring Affordable Housing to be produced, may provide immediate and lasting benefits to communities across the City and region.

Bibliography

Richman, S., Donoghue, D., Saunders, L., Ames, R., Anthony, S., Ash, P., Bernier, A., Bobb, R., Bonar, J., Boyle., R., Breidenbach, J., Brighouse, S., Brighouse, J., Bruguera, S., Butcher, J., Cantrell, D., Clemens, P., Coronel, Y., Crawford, A., DeGon, K...Wilson, B. (2000). In Short Supply: Recommendations of the Los Angeles Housing Crisis Task Force. Los Angeles City Council.

Baker, K., Baldwin, P., Donahue, K., Flynn, A., Herbert, C., La Jeunesse, E., Lancaster, M., Lew, I., Manning, K., Marya, E., McCue, D., Molinsky, J., Sanchez-Moyano, R., von Hoffman, A., Will, A., Alexander, B., Apgar, W., Berman, M., Bratt, R., Carliner, M...Richardson, R. (2015). The State of the Nation's Housing. Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University.

Morrow, G. (2013). The Homeowner Revolution: Democracy, Land Use and the Los Angeles Slow-Growth Movement, 1965-1992. (Doctoral Dissertation, UCLA). Proquest Dissertations And Theses Global.

Monkkonen, P., Lens, M., Manville, M. (2020). Built Out Cities: How California Cities Restrict Housing Production Through Prohibition and Process. Terner Center for Housing Diversity. 3 - 20. https://ternercenter.berkeley.edu/research-and-policy/built-out-cities-how-california-cities-restrict-housing-production-through-prohibition-and-process/

Woetzel, J., Ward, T., Peloquin, S., Kling, S., Arora, S. (2019). Affordable Housing in Los Angeles: Delivering more - and doing it faster. McKinsey Global Institute.

Franco, J & Mitchell, B. Dr. HOLC “redlining” Maps: The Persistent Structure of Segregation and Income Inequality. National Community Reinvestment Coalition. 2-28. https://ncrc.org/wp-content/uploads/dlm_uploads/2018/02/NCRC-Research-HOLC-10.pdf

Taylor, M. (2015). California's High Housing Costs: Causes and Consequences. Legislative Analyst’s Office. https://homeforallsmc.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/housing-costs.pdf

Brooks, A., Raitt, J., Coleman, A., Loughlin, B., Eddington, T., Frost., B., Levine, M., Murphy, K., Sickles, M. (2019). Housing Policy Guide. American Planning Association.

Eikel, M. (1973). Zoning Shall be Consistent with the General Plan. San Diego Law Review, Volume 10, 901.

Lewis, P. (2003). California's Housing Element Law: The Issue of Local. San Public Policy Institute of California

Brown, E., Podesta, A., Metcalf, B. (2017). California's Housing Future: Challenges and Opportunities.

Ling, S. (2018). How Fair is Fair-Share? A Longitudinal Assessment of California's Housing Element Law. (Masters Thesis, UCLA). Proquest Dissertations And Theses Global.

Knaap, G., Meck, S., Moore, T., Parker, R. (2007). Zoning as a Barrier to Multifamily Housing Development. American Planning Association.

Cervero, R. & Duncan, M. (2004). Neighborhood Composition and Residential Land Prices: Does Exclusion Raise or Lower Values. Cairfax Publishing.

Kahlenberg, R. (2017). An Economic Fair Housing Act. The Century Foundation.

Cosman, J. & Quintero, L. (2019). Fewer players, fewer homes: concentration and the new dynamics of housing supply. Carey Business School & Johns Hopkins University.

Mischke, J., Peloquin, S., Weisfield, D., Woetzel, J. (2016). Closing California's Housing Gap. McKinsey Global Institute

Lee, D. (2017). How AirBNB Short Term Rentals Exacerbate Los Angeles’s Affordable Housing Crisis. Harvard Law and Policy Review, Volume 10, 229.

Nelson, G., Stefancic, A., Rae, J., Townley, G., Tsemberis, S., Macnaughton, E., . . . Goering, P. (2014). Early Implementation Evaluation of a Multi-Site Housing First Intervention for Homeless People with Mental Illness. Journal of Evaluation and Program Planning, 43, 16- 26. doi:10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2013.10.004

Ecker, J., & Aubry, T. (2017). A Mixed Methods Analysis of Housing and Neighbourhood Impacts on Community Integration Among Vulnerably Housed and Homeless Individuals. Journal of Community Psychology, 45(4), 528-542. doi:10.1002/jcop.21864

Graves, E.M. (2011). Mixed Outcome Developments. Journal of the American Planning Association, 77(2), 143-153. doi:10.1080/01944363.2011.567921

Regional Housing Needs Assessment. (2020, December 10). https://scag.ca.gov/housing-elements.

Rodman-Alvarez D., Mattheis-Brown, R., Ricardo de la Rosa, L. (2020). Areas of Net Loss in Dwelling Units in Los Angeles. Pacific Urbanism.

Garcetti, E. (2021, February 18). Summary of HHH Projects in Development. https://www.lamayor.org/summary-hhh-projects-development.

Bertoni V. (2021, February 18) Housing Progress Dashboard. https://planning.lacity.org/resources/housing-reports.

Nisar, et al. (2019). Market Predictors of Homelessness: How Housing and Community Factors Shape Homelessness Rates Within Continuums of Care. Accessed online: https://www.huduser.gov/portal/publications/Market-Predictors-of-Homelessness.html#:~:text=The%20study%20finds%20that%20housing,rates%20of%20community%2Dlevel%20homelessness.