Residential Land Use and Zoning

1958 TO 2015 and Beyond IN COUNCIL DISTRICT 1 AND THE CITY OF LOS ANGELES

Introduction

California law requires each municipality to prepare and adopt a residential land use plan and associated zoning map that allows for production of a certain share of the State’s overall projected housing need. Projected housing needs for the State are allocated by region and updated every eight years under the Regional Housing Needs Assessment targets (RHNA targets). The City of Los Angeles has recently updated the Housing Element of its General Plan in response to the 2029 RHNA target that requires just under half a million (456,643) net new homes by 2029. Net new homes refers to the resultant supply of dwelling units once loss due to demolition or conversion are taken into account. While updates to the current City of Los Angeles Zoning Map are underway, the crucial issue of fair and equitable distribution of housing within the City of Los Angeles as well as the legacy of racial, ethnic, and economic exclusionism in land use policies ought to be confronted.

This report addresses the need for a fair and equitable method for allocating the 2029 RHNA target within the 37 Community Plan Areas (CPAs) of the City of Los Angeles. 35 CPAs, excluding Los Angeles International Airport CPA and the Port of Los Angeles CPA, are planned for residential land use among their planned land uses.

Whereas previous Zoning regimes have failed to direct the supply of dwelling units where housing is best suited, recent academic work in the field has explored spatial analysis of likelihood for development. However, this report fills a gap in the scholarly and policy literature on Los Angeles zoning and housing allocation to explore a normative state, that is, where housing ought to be.

A second aim of this report is to report housing targets by City Council District and to shift the language from zoning classifications, which can be abstract and obfuscate the intended land use result, to density in units of DU/Ac and then to a Building Typology classified by the number of dwelling units per building or project.

Literature Review

A growing body of academic and policy literature continues to document and evaluate the various root causes of the California housing shortage and the Los Angeles housing crisis in particular.

Whittemore (2012) synthesizes the various attitudes towards zoning in los angeles from 1909 through 2012 into four eras, or regimes: 1) hegemony of speculative real estate interests ending with the collapse of the 1920s bubble 2) mid 1930s through mid 1960s suburban single family residential development supported by Federal Housing Administration (FHA) programs, 3) 1960s through 2000s slow-growth or no-growth, and 4) the current era post 2000. Unfortunately, empirical data from the 2000s onwards challenges Whittemore’s notion that a new era post slow-growth or no-growth had commenced, but rather, evidence suggests that the attitudes towards zoning among decision makers and professional planners in the City of Los Angeles continue to favor to slow-growth/ no-growth paradigm.

Greg Morrow (2013) describes the history and challenges of the paradigm shift within the third era of zoning regimes, from the Watts uprising to the Rodney King civil unrest, in which the planned population of the City of Los Angeles was downzoned by 60%, from 10 million down to roughly 4 million.

Kahlenberg (2017) explores the adverse effects that exclusionary zoning has had on populations, including unequal access to quality schools, which is a determinant of public health outcomes.

Roman-Alvarez (2020) reports a new method for using empirical data that is geographically located to create a composite index score the Housing Allocation Index (HAI) that accounts for housing unaffordability, environmental health, transit quality, historic downzoning, and opportunities, such as school quality and number of jobs. The HAI is a data driven tool that objectively distributes the 2029 RHNA target into the 35 CPAs with residentially zoned land.

Methods

Average Density of Dwelling Units per Acre in the City of Los Angeles

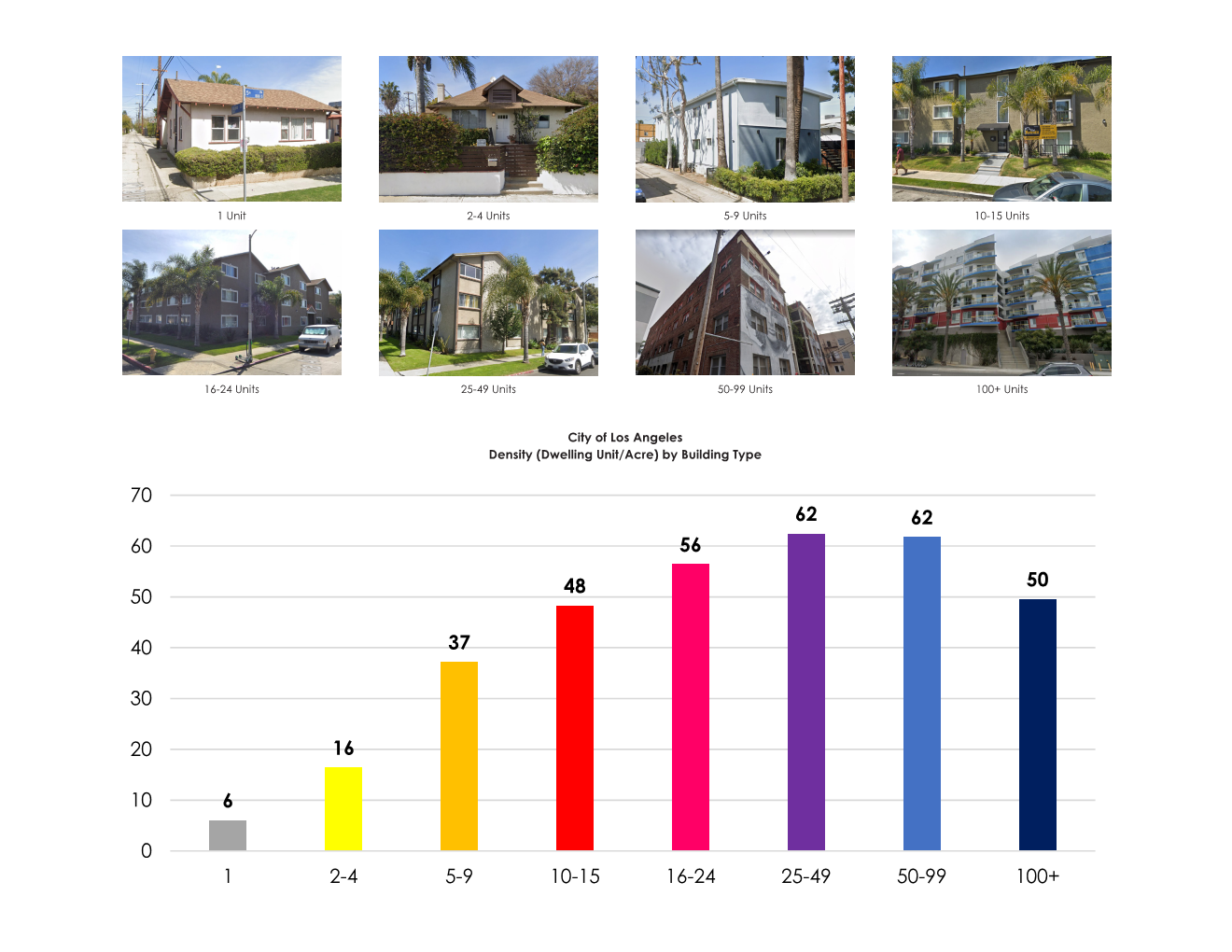

Existing dwelling units in the City of Los Angeles were organized into a Building Typology according to the number of units in the building or project. The subtotal number of units by the typology classification were divided by the sum area of land in acres. Each density in DU/Ac by Building Typology classification is reported.

1958, 2020, and 2029 Planned Land Use and Zoning Maps

A shapefile of the 1958 Zoning Map for the City of Los Angeles was prepared using ESRI ArcMap tools and physical records from the Department of City Planning [Insert Figure]. Land by its 1958 zoning classification was drafted and assigned an attribute field to match the reported classification label. The current zoning map and City Council Districts (CD) shapefiles were downloaded from the City of Los Angeles Geohub portal.

The 2029 land use map was used applying the methods of the HAI (Rodman-Alvarez, 2020), then intersecting with the shapefile for CD. Existing dwelling unit counts for each land use area were prepared using US Census Bureau data at the census tract scale. Then, the portion of the 2029 RHNA target that corresponds to each land use area was added to the existing number of dwelling units in order to arrive at a grand total target of dwelling units. The grand total of existing dwelling units plus 2029 RHNA target was divided by the acres for each swath of land in order to arrive at a target density in DU/Ac, which was then associated with the Building Typology that is applicable to the resultant target density. The purpose of reporting Target Density and Building Type, as opposed to zoning classification is to remove the abstraction of zoning classifications, such as R3 zones or R4 zones, and communicate plainly the average building type that would accomplish the aggregate number of dwelling units required for each swath of land.

Results

Discussion, Conclusions, and Areas for Further Research

At its root, the housing shortage is a result of 50 to 60 years of exclusionary zoning policies that have limited the allowable supply of dwelling units in many areas of high housing demand. Housing supply has declined in the City of Los Angeles from a high of just under 300,000 net new dwelling units in the decade of the 1950s to a low of just over 37,000 in the decade of the 1990s. Whereas the housing supply of the decade of the 2010s represents an increase of 13% from the previous decade of the 2000s and a 120% increase from the low of the 1990s, housing supply of the 2010s is close to simply a quarter of the rate of supply of the 1950s, or a 72% reduction.

A paradigmatic is necessary as some language used in discussions regarding the supply of dwelling units is stigmatized, such as development and density. The existing housing stock of roughly 1.4 million dwelling units in the City of Los Angeles ranges in average density of dwelling units per acre (DU/Ac) from a value of 6 DU/Ac for the 584,673 single family dwellings on 97,642 acres of land to 62 DU/Ac for the 122,699 dwelling units in buildings with between 25 to 49 units, which is a relatively low density compared to some building typologies. However, some policy discussions are limited by their use of a 10, 20, 30 DU/Ac rubric when categorizing low, medium, and high density.

Now, with the required half-million net new dwelling units by 2029 in the City of Los Angeles, a special opportunity is presented from which previously underserved communities may benefit: an equitable distribution of housing that addresses a range of inequities that have resulted from decades of exclusionary zoning practices and other constraints on a healthy supply of housing. As it pertains to zoning, truly modest policy changes are capable of producing substantially transformative results to the benefit of the Los Angeles community at large.

Last, this report lays a foundation for further questions to be raised, such as, who gets to define the normative state? Who stands to benefit? And at the expense of whom?

Bibliography

California Department of Housing and Community Development. (2017). California's Housing Future: Challenges and Opportunities.

Cervero, Robert. Duncan, Michael. (2004). Neighborhood Composition and Residential Land Prices: Does Exclusion Raise or Lower Values. Cairfax Publishing.

Eikel, Mary. (1973). Zoning Shall be Consistent with the General Plan. San Diego, California: San Diego Law Review.

Elmendorf, Christopher S. Biber, Eric. Monkkonen, Paavo. O'Neill, Moira. (2019). Making It Work: Legal Foundations for Administrative Reform of California's Housing Framework. Davis, CA: UC Davis School of Law

Housing Crisis Task Force. (2000). In Short Supply, Recommendations of the Los Angeles Housing Crisis Task Force. Los Angeles, California.

Khalenberg, Richard D. (2017). An Economic Fair Housing Act. The century Foundation.

Knaap, Gerrit, Meck, Stuart, Moore, Terry, and Robert Parker. (2007). Zoning as a Barrier to Multifamily Housing Development. Chicago, Illinois: American Planning Association.

Lewis, Paul G. (2003). California's Housing Element Law: The Issue of Local. San Francisco, CA: Public Policy Institute of California.

Ling, Shine. (2018) . How Fair is Fair-Share? A Longitudinal Assessment of California's Housing Element Law. Los Angeles, California: UCLA.

Morrow, Greg. (2013). The Homeowner Revolution: Democracy, Land Use and the Los Angeles Slow-Growth Movement, 1965-1992. Los Angeles, California: UCLA.

Rodman-Alvarez, Dario et al. (2020) The Housing Allocation Index to Meet the 2029 RHNA Targets for the City of Los Angeles by Community Plan Area. Los Angeles, CA. Pacific Urbanism. Retrieved from https:// www.pacificurbanism.org/publications.

Taylor, Mac. (2015). California's High Housing Costs, Causes and Consequences. Legislative Analyst’s Office

The State of the Nation's Housing. (2015). Cambridge, MA: President and Fellows of Harvard College

Whittemore, Andrew H. (2012): Zoning Los Angeles: a brief history of four regimes, Planning Perspectives, 27:3, 393-415